After last summer’s hunt in a council car park for the bones of King Richard III, feature writer Sally Jack travels through time to consider media interest in this infamous 15th century monarch and its impact on Leicester.

August 25 1485: Three, maybe four Fransican monks from Greyfriars Friary took care of a body. The Friary was insignificant compared to the nearby royal favourite Church of St Mary de Castro. However, the body was interred near the choir, a place usually reserved for those with high status in medieval society. The Grey Friars worked carefully but quickly and the body buried without a coffin.

Fast forward to August 25 2012 where three, maybe four archaeologists from the University of Leicester began excavations in a city centre car park. The Richard III Society had instigated a collaboration between themselves, Leicester City Council and the university to search a potential site for the last resting place of King Richard III.

Archaeologists referred to new research and contemporary accounts indicating the infamous king was buried in the choir of Greyfriars Friary, followed by a press release announcing the dig. King Richard was back in the news and the rest was history, literally.

Days after the dig began a skeleton was found. Key figures from the dig team held a press conference in Leicester’s 14th century Guildhall to reveal dramatic new findings including the significant news the skeleton had a curved spine and mysteriously, its feet were missing. Furthermore, this discovery may never have happened at all had Victorian builders dug deeper. Excavations revealed 19th century foundations thirty centimetres from the remains – another spadeful and all evidence would have been destroyed.

Relatives of King Richard’s elder sister Anne of York were traced to provide DNA samples. Analysis on the skeleton began and DNA profiling techniques, pioneered in the 1980s by Sir Alec Jeffreys at the University of Leicester, were used on the remains. Although analysis results may not be known until early 2013 there is no doubt events of August 25 in both the 15th and 21st centuries renewed interest not only in the last King of England to die in battle, but also in Leicester.

Leicester and Leicestershire Enterprise Partnership (LLEP) chairman Andrew Bacon refers to ‘the Richard factor’. He said: “If the remains turn out to be those of King Richard III, Leicester and Leicestershire stand to benefit from a multi-million pound economic boost as tourists from across the globe visit the area.”

Television crews from as far as Australia swarmed around the city’s streets in the late summer sun, capturing growing queues of visitors hoping for a glimpse of the dig site.

Reflecting on this sudden media interest, Richard Taylor, director of Corporate Affairs and Planning at the University of Leicester said: “The news went viral: there were around a quarter of a million mentions of Richard III in the 48 hours after the announcement on Twitter. It trended at one point. We had around 350 news articles including Time Magazine, Sydney Morning Herald and the Times of India.”

Along with thousands of tweets, website hits and media mentions, Leicester City Council estimates around 10,000 people visited the dig site and artefact exhibition on the three weekends they were open to the public.

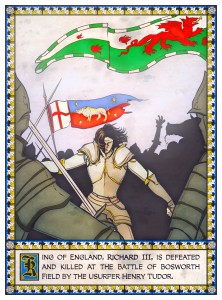

The 15th century version of a press release was a little more sinister. It was in victorious Henry Tudor’s interests to let England know Richard was dead, the War of the Roses was over and the country was entering the reign of the Tudors. Richard’s naked and broken body was brought back from Bosworth slung across a horse and as further warning, the dead king’s body was hung on public display in Leicester – a grisly sight but necessary to avoid speculation Richard would return to regain the crown.

Leicester’s associations with Richard are more closely linked with events leading up to his death. Richard had previously visited the city staying at Leicester Castle, a popular residence for nobility. However, on the night of August 19 1485, three days before the Battle of Bosworth, King Richard did not stay there but at the White Boar Inn (then the Blue Boar Inn after the battle, now the site of the Travelodge, Highcross Street). This was more a reflection of the speed at which Richard had to react to news that Henry Tudor had landed at Milford Haven to challenge the throne.

His army of 2,000 increased as he marched through the Midlands amassing archers and foot soldiers from Lancastrian strongholds. Messages passed between the two camps

by heralds on horseback and summoning his supporters, King Richard travelled from Nottingham Castle to Leicester to intercept the usurper. With an estimated army of 8,000 he was confident of victory.

A royal visit, whatever the reason always attracts interest. In March 2012 thousands lined the streets of Leicester, eager to see Queen Elizabeth II begin her Diamond Jubilee tour in the city, her every move punctuated by flashes from mobiles and cameras.

Few records document Richard’s march from Leicester to Bosworth. In 1485 crowds might have jostled for a good view of their king as he led his Royal Army down Highcross Street towards Bow Bridge and over the Soar to Market Bosworth. Watching from the West Gate you may have witnessed the snort and stamp of horses, heard cheers from the crowd and knights’ orders to proceed. Heralds dashed between men preparing for battle, armour glinted in the early morning sun and all set to the rhythm of a steady drumbeat.

Banners of St George flew alongside the king’s standard displaying his emblem of a white boar and the white rose of York. With his men mustered for battle, King Richard III in full armour and golden crown mounted his white horse and left Leicester for the last time.

Events at Bosworth Battlefield are of great historical importance and the visitor centre at the site is a poignant reminder of a bloody and ferocious battle, all over in little more than an hour. News of the dig generated a resurgence of interest in the Battle of Bosworth with an increase of 30% in visitor numbers reported during September.

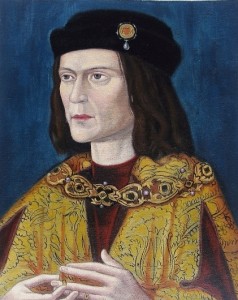

From late August 1485 onwards the image of King Richard III was in the hands of the Tudors – as their dynasty began so too the might of their media machine. Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the Third portrayed Richard as a hunchbacked murderer and few argued with lines such as “God and good angels fight on Richmond’s [Henry Tudor] side; and Richard falls in height of all his pride.”

From late August 1485 onwards the image of King Richard III was in the hands of the Tudors – as their dynasty began so too the might of their media machine. Shakespeare’s The Tragedy of King Richard the Third portrayed Richard as a hunchbacked murderer and few argued with lines such as “God and good angels fight on Richmond’s [Henry Tudor] side; and Richard falls in height of all his pride.”

Perhaps because we find a villain more interesting this image of Richard has stuck. Before Richard assumed the crown of England in 1483 he was a popular figure, a skilled soldier and statesman. However, like many throughout history, power corrupts and Richard was certainly in the thick press of political manoeuvres. Several of his loyal supporters were executed, the princes in the tower – Richard’s nephews – disappeared.

This combined with the medieval view that physical abnormalities were linked negatively with character meant although many events have never been proven, Richard’s reputation was set indelibly in Shakespeare’s ink.

The term ‘spin’ might be considered a 20th century media phenomenon yet the concept has been around ever since humans have spoken to one another. The life and death of King Richard III is laced with half a millennium’s worth of myth and legend – the Tudor spin doctors did a good job.

Nowadays, historical records are subject to rigorous scientific analysis yet it is the combination of fact and propaganda which has made King Richard III so fascinating to the world.

LLEP board member and city mayor Sir Peter Soulsby said: “Leicester’s rich heritage has long been undersold but it has a huge role to play in the promotion of our city. There has been world-wide interest in the Richard III story and we are already looking at how we can build on this to the benefit of the city and county.”

The dig for King Richard III has demonstrated how managing our heritage is of vital economic and cultural importance. Stuart Bailey, chairman of Leicester Civic Society commented: “The 15th century can be used to develop Leicester in the 21st century, using what we have left to us as heritage-led regeneration.”

It can only be speculated as to how Leicester might benefit should the skeleton in the car park turn out to be England’s last Plantagenet monarch. This chapter of the story of Leicester is yet to be written.